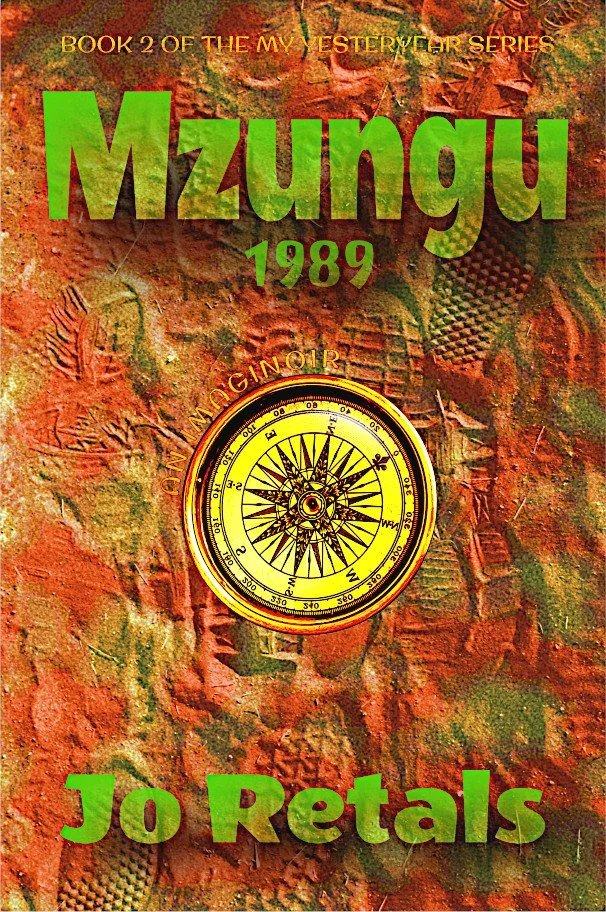

Story

“A moonlit vision on Mt. Kenya propels an American expatriate into a collision of faith, family, and ambition.”

Jo Retals escaped Pennsylvania for the Kenyan Highlands.

When a mountaintop vision heralds a new adventure, local politics and workplace obligations force a life defining choice — an extraordinary life for his family now, or an extraordinary opportunity for a prestigious future.

Background

-

Set in rural Kenya during the end of the Cold War, Mzungu 1989 explores how cultural and institutional narrative impacts personal agency.

In the age of Glasnost and Perestroika, the Soviet Union is shedding the constraints of Marxist ideology. In Kenya urbanization forces high profile challenges to traditional culture.

In Mzungu 1989, graduate work and job reassignment force the narrator to confront local tradition and the dogmas of his faith. Yet, he discovers that his own culture can be blinded by ideology.

-

Mzungu 1989 is an Adventure novel, narrated by a confident family man living an extraordinary life. At the nexus of contract conclusion and graduate degree completion, he must discover his next adventure. Can he maintain an extraordinary life?

The author’s internal journey is a status story. The narrator investigates an insight about his community and society. Will academic credentials automatically invest him with the respect he craves?

Based on actual events from the author’s life, Mzungu 1989 weaves complementary storylines – one a formal interview, and the other a personal letter.